The goal of SparseNUTS is to provide a user-friendly workflow for users of TMB and RTMB who want to implement the sparse no-u-turn sampler (C. C. Monnahan et al. in prep) to draw samples from a model.

This package was originally developed inside of the adnuts package

but was split off in late 2025 to have a dedicated package for

SparseNUTS for TMB and RTMB models. The tmbstan package

also provides an interface to the Stan software, but lacks the ability

to decorrelate the target distribution prior to sampling.

SparseNUTS provides more flexible options related to the

mass matrix.

Differences in usage between TMB and RTMB

Both TMB and RTMB models can be used with minimal user intervention,

including running parallel chains. The sample_snuts

function will detect which package is used internally and adjust

accordingly. If the user wants to use models from both packages in the

same session then one needs to be unloaded, e.g.,

if('TMB' %in% .packages()) detach(package:TMB), before the

other package is loaded.

If the RTMB model uses external functions or data sets then they must

be passed through via a list in the globals argument so

they are available to rebuild the ‘obj’ in the parallel R sessions.

Optionally, the model_name can be specified in the call,

otherwise your model will be labeled “RTMB” in the output. TMB models do

not require a globals input and the model name is pulled from the DLL

name, but can be overridden if desired.

Comparison to tmbstan

The related package ‘tmbstan’ (C. C. Monnahan

and Kristensen 2018) also allows users to link TMB models to the

Stan algorithms. ‘tmbstan’ links through the package ‘rstan’, while

‘SparseNUTS’ modifies the objective and gradient functions and then

passes those to ‘cmdstan’ through the ‘StanEstimators’ R package

interface. For models without large correlations or scale differences,

tmbstan is likely to be faster than ‘SparseNUTS’ due to

lower overhead and may be a better option. Eventually, Stan may add

SNUTS functionality and an interface to ‘tmbstan’ developed, and in that

case tmbstan may be a better long term option. For TMB

users now, SNUTS via SparseNUTS is likely to be the best

overall package for Bayesian inference.

SNUTS for TMB models from existing packages (sdmTMB, glmmTMB, etc.)

SparseNUTS works for custom TMB and RTMB models

developed locally, but also for those that come in packages. Most

packages will return the TMB ‘obj’ which can then be passed into

sample_snuts.

For instance the glmmTMB package can be run like

this:

library(glmmTMB)

library(SparseNUTS)

data(Salamanders)

obj <- glmmTMB(count~spp * mined + (1|site), Salamanders, family="nbinom2")$obj

fit <- sample_snuts(obj)Basic usage

The recommended usage for TMB users is to let the

sample_snuts function automatically detect the metric to

use and the length of warmup period, especially for pilot runs during

model development.

I demonstrate basic usage using a very simple RTMB version of the eight schools model that has been examined extensively in the Bayesian literature. The first step is to build the TMB object ‘obj’ that incorporates priors and Jacobians for parameter transformations. Note that the R function returns the negative un-normalized log-posterior density.

library(RTMB)

library(SparseNUTS)

dat <- list(y=c(28, 8, -3, 7, -1, 1, 18, 12),

sigma=c(15, 10, 16, 11, 9, 11, 10, 18))

pars <- list(mu=0, logtau=0, eta=rep(1,8))

f <- function(pars){

getAll(dat, pars)

theta <- mu + exp(logtau) * eta;

lp <- sum(dnorm(eta, 0,1, log=TRUE))+ # prior

sum(dnorm(y,theta,sigma,log=TRUE))+ #likelihood

logtau # jacobian

REPORT(theta)

return(-lp)

}

obj <- MakeADFun(func=f, parameters=pars,

random="eta", silent=TRUE)Posterior sampling with SNUTS

The most common task is to draw samples from the posterior density

defined by this model. This is done with the sample_snuts

function as follows:

fit <- sample_snuts(obj, refresh=0, seed=1,

model_name = 'schools',

cores=1, chains=1,

globals=list(dat=dat))## Optimizing...## Getting Q...## Inverting Q...## Q is 62.22% zeroes, with condition factor=56 (min=0.044, max=2.5)## Rebuilding RTMB obj without random effects...## diag metric selected b/c of low correlations (max=0.2927)## log-posterior at inits=(-34.66); at conditional mode=-34.661## Starting MCMC sampling...##

##

## Gradient evaluation took 8.2e-05 seconds

## 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.82 seconds.

## Adjust your expectations accordingly!

##

##

##

## Elapsed Time: 0.098 seconds (Warm-up)

## 0.605 seconds (Sampling)

## 0.703 seconds (Total)

##

##

##

## Model 'schools' has 10 pars, and was fit using NUTS with a 'diag' metric

## 1 chain(s) of 1150 total iterations (150 warmup) were used

## Average run time per chain was 0.7 seconds

## Minimum ESS=265.6 (26.56%), and maximum Rhat=1.003

## There were 0 divergences after warmupThe returned object fit (an object of ‘adfit’ S3 class)

contains the posterior samples and other relevant information for a

Bayesian analysis.

Here a ‘diag’ (diagonal) metric is selected and a very short warmup period of 150 iterations is used, with mass matrix adaptation in Stan disabled. See below for more details on mass matrix adaptation within Stan.

Notice that no optimization was done before calling

sample_snuts. When the model has already been optimized,

you can skip that by setting skip_optimization=TRUE, and

even pass in

and

via arguments Q and Qinv to bypass this step

and save some run time. This may also be required if the model

optimization routine internal to sample_snuts is

insufficient. In that case, the user should optimize prior to SNUTS

sampling. The returned fitted object contains a slot called

mle (for maximum likelihood estimates) which has the

conditional mode (‘est’), the marginal standard errors ‘se’, a joint

correlation matrix (‘cor’), and the sparse precision matrix

.

str(fit$mle)## List of 5

## $ nopar: int 10

## $ est : Named num [1:10] 7.92441 1.8414 0.47811 0.00341 -0.2329 ...

## ..- attr(*, "names")= chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## $ se : Named num [1:10] 4.725 0.732 0.959 0.872 0.945 ...

## ..- attr(*, "names")= chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## $ cor : num [1:10, 1:10] 1 0.0558 -0.1031 -0.2443 -0.114 ...

## ..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

## .. ..$ : chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## .. ..$ : chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## $ Q :Formal class 'dsCMatrix' [package "Matrix"] with 7 slots

## .. ..@ i : int [1:27] 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ...

## .. ..@ p : int [1:11] 0 10 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 ...

## .. ..@ Dim : int [1:2] 10 10

## .. ..@ Dimnames:List of 2

## .. .. ..$ : chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## .. .. ..$ : chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## .. ..@ x : num [1:27] 0.0603 -0.0144 0.028 0.0631 0.0246 ...

## .. ..@ uplo : chr "L"

## .. ..@ factors :List of 1

## .. .. ..$ SPdCholesky:Formal class 'dCHMsuper' [package "Matrix"] with 10 slots

## .. .. .. .. ..@ x : num [1:100] 1.06 0 0 0 0 ...

## .. .. .. .. ..@ super : int [1:2] 0 10

## .. .. .. .. ..@ pi : int [1:2] 0 10

## .. .. .. .. ..@ px : int [1:2] 0 100

## .. .. .. .. ..@ s : int [1:10] 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

## .. .. .. .. ..@ type : int [1:6] 2 1 1 1 1 1

## .. .. .. .. ..@ colcount: int [1:10] 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 3 2 1

## .. .. .. .. ..@ perm : int [1:10] 9 8 7 6 5 4 0 2 3 1

## .. .. .. .. ..@ Dim : int [1:2] 10 10

## .. .. .. .. ..@ Dimnames:List of 2

## .. .. .. .. .. ..$ : chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## .. .. .. .. .. ..$ : chr [1:10] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...Diagnostics

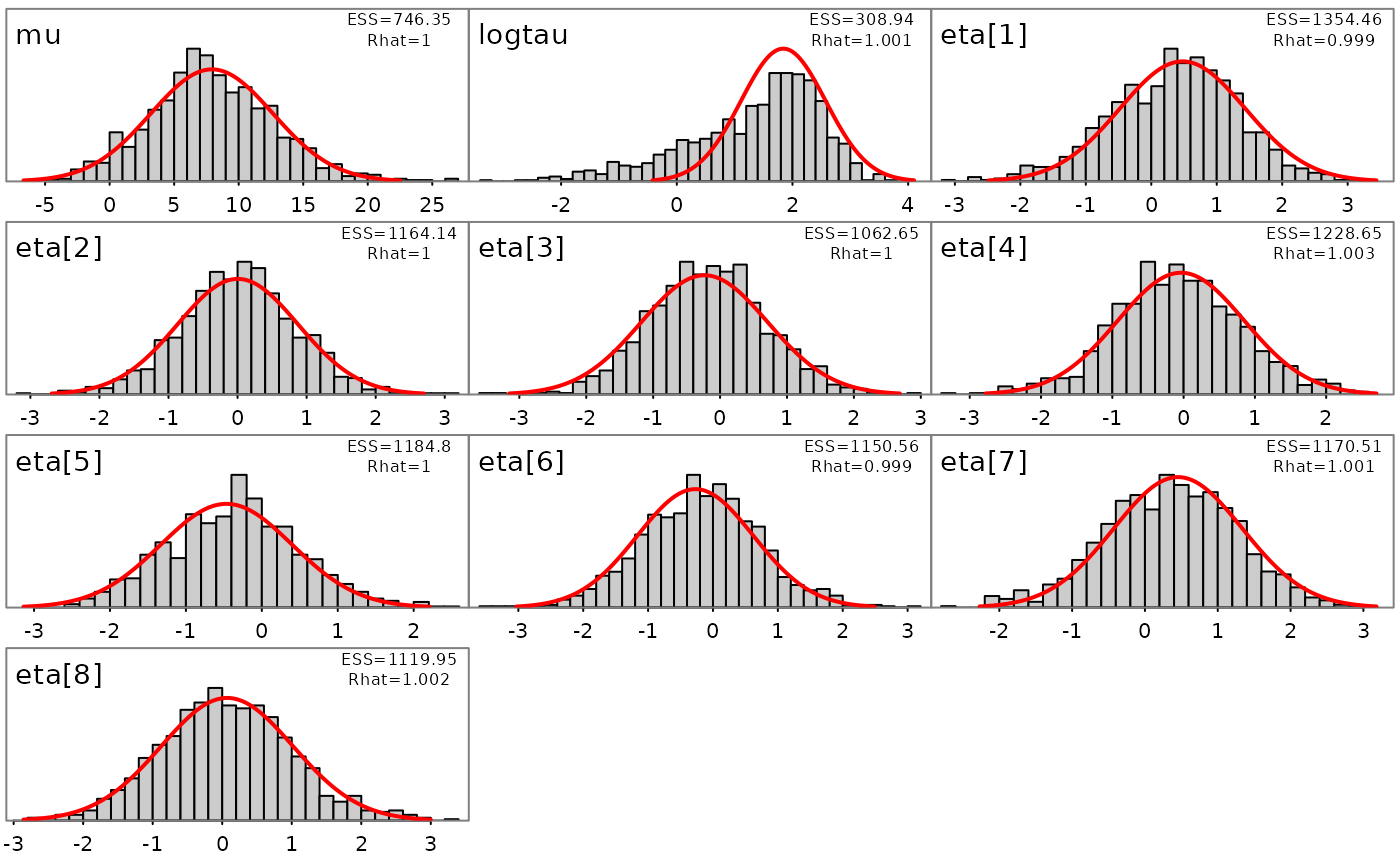

The common MCMC diagnostics potential scale reduction (Rhat) and

minimum ESS, as well as the NUTS divergences (see diagnostics

section of the rstan manual), are printed to console by default or

can be accessed in more depth via the monitor slot:

print(fit)## Model 'schools' has 10 pars, and was fit using NUTS with a 'diag' metric

## 1 chain(s) of 1150 total iterations (150 warmup) were used

## Average run time per chain was 0.7 seconds

## Minimum ESS=265.6 (26.56%), and maximum Rhat=1.003

## There were 0 divergences after warmup

fit$monitor |> str()## drws_smm [11 × 10] (S3: draws_summary/tbl_df/tbl/data.frame)

## $ variable: chr [1:11] "mu" "logtau" "eta[1]" "eta[2]" ...

## $ mean : num [1:11] 7.8963 1.3284 0.3436 0.0114 -0.1834 ...

## $ median : num [1:11] 7.5789 1.6113 0.399 0.0223 -0.1674 ...

## $ sd : num [1:11] 4.767 1.161 0.972 0.834 0.863 ...

## $ mad : num [1:11] 4.513 1.051 0.989 0.782 0.84 ...

## $ q5 : num [1:11] 0.246 -1.01 -1.286 -1.344 -1.569 ...

## $ q95 : num [1:11] 15.75 2.82 1.85 1.36 1.26 ...

## $ rhat : num [1:11] 1 1.001 0.999 1 1 ...

## $ ess_bulk: num [1:11] 746 309 1354 1164 1063 ...

## $ ess_tail: num [1:11] 534 502 692 704 603 ...

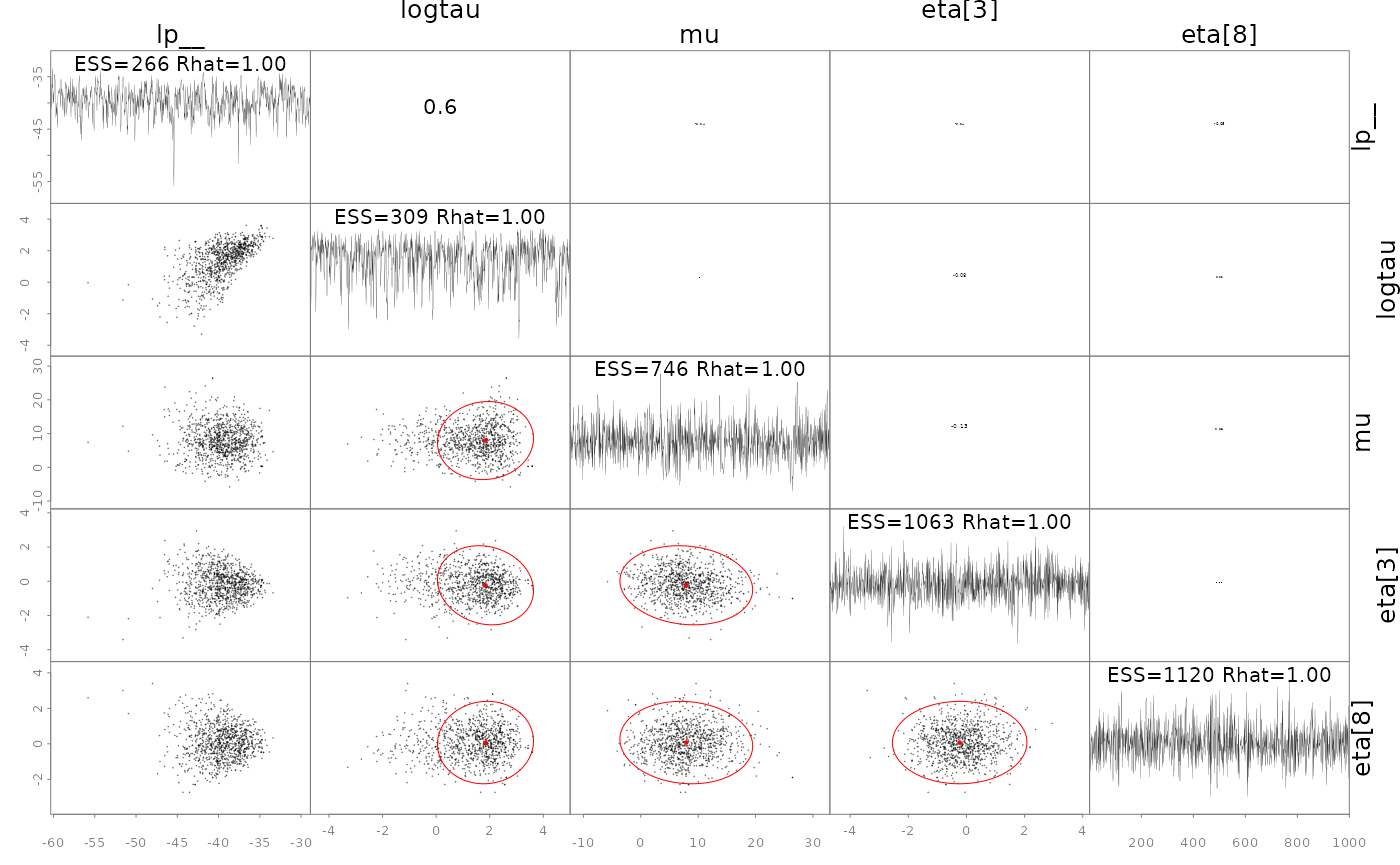

## - attr(*, "num_args")= list()A specialized pairs plotting function is available

(formally called pairs_admb) to examine pair-wise behavior

of the posteriors. This can be useful to help diagnose particularly slow

mixing parameters. This function also displays the conditional mode

(point) and 95% bivariate confidence region (ellipses) as calculated

from the approximate covariance matrix

.

The parameters to show can be specified either vie a character vector

like pars=c('mu', 'logtau', 'eta[1]') or an integer vector

like pars=1:3, and when using the latter the parameters can

be ordered by slowest mixing (‘slow’), fastest mixing (‘fast’) or by the

largest discrepancies in the approximate marginal variance from

and the posterior samples (‘mismatch’). NUTS divergences are shown as

green points. See help and further information at

?pairs.adfit.

pairs(fit, order='slow')

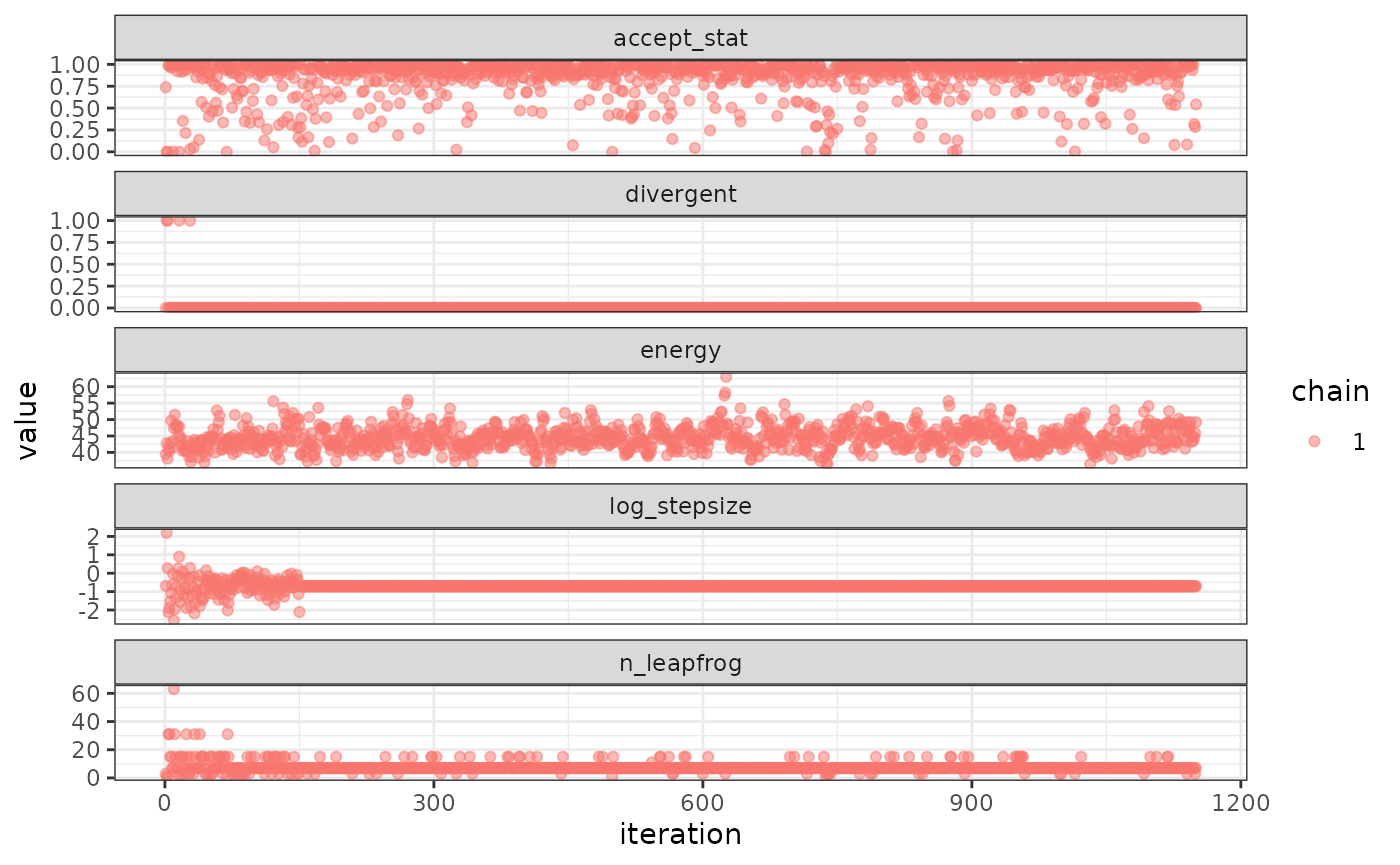

In some cases it is useful to diagnose the NUTS behavior by examining the “sampler parameters”, which contain information about the individual NUTS trajectories.

extract_sampler_params(fit) |> str()## 'data.frame': 1000 obs. of 8 variables:

## $ chain : num 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ iteration : num 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 ...

## $ accept_stat__: num 0.281 0.384 0.116 0.781 0.945 ...

## $ stepsize__ : num 0.492 0.492 0.492 0.492 0.492 ...

## $ treedepth__ : num 3 3 3 2 3 3 3 2 2 3 ...

## $ n_leapfrog__ : num 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 7 ...

## $ divergent__ : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ energy__ : num 39.3 39.5 41.9 44.3 45.6 ...

## or plot them directly

plot_sampler_params(fit)

The ShinyStan tool is also available and provides a convenient,

interactive way to check diagnostics via the function

launch_shinytmb(), but also explore estimates and other

important quantities. This is a valuable tool for a workflow with

‘SparseNUTS’.

Bayesian inference

After checking for signs of non-convergence the results can be used

for inference. Posterior samples for parameters can be extracted and

examined in R by casting the fitted object to an R data.frame. These

posterior samples can then be put back into the TMB object

obj$report() function to extract any desired “generated

quantity” in Stan terminology. Below is a demonstration of how to do

this for the quantity theta (a vector of length 8).

post <- as.data.frame(fit)

post |> str()## 'data.frame': 1000 obs. of 10 variables:

## $ mu : num 12.01 9.87 4.4 10.34 4.88 ...

## $ logtau: num 3.328 3.605 -1.271 -0.259 2.178 ...

## $ eta[1]: num 1.026 1.319 -0.646 -2.113 -0.642 ...

## $ eta[2]: num 0.513 -0.215 0.132 0.175 0.961 ...

## $ eta[3]: num 0.04341 -0.44468 -0.01319 -0.30872 -0.00504 ...

## $ eta[4]: num -0.0476 -0.3879 -0.2872 -1.1967 -0.4708 ...

## $ eta[5]: num -0.224 -0.444 -0.3 -0.39 -1.31 ...

## $ eta[6]: num -0.2575 -0.511 -0.5113 -0.7201 0.0883 ...

## $ eta[7]: num 0.2236 -0.0579 0.8496 0.0664 1.136 ...

## $ eta[8]: num -0.216 0.422 -0.479 -0.726 -1.365 ...

## now get a generated quantity, here theta which is a vector of

## length 8 so becomes a matrix of posterior samples

theta <- apply(post,1, \(x) obj$report(x)$theta) |> t()

theta |> str()## num [1:1000, 1:8] 40.606 58.386 4.221 8.714 -0.787 ...Likewise, marginal distributions can be explored visually and compared to the approximate estimate from the conditional mode and (red lines):

plot_marginals(fit)